By Lula Davis and Laila Henderson

In 1815, an unnamed, healthy baby girl was born to slaves on the James Island plantation in South Carolina. Around the fourth week of her life, a small tumor formed behind the baby’s right ear. Elias S. Bennett, medical student and son of the plantation owner, was anxious to remove the tumor with the assistance of his fellow student, Dr. Malcomson. The surgery was unsuccessful as the two hit the white matter—also known as substantia alba—a central component nervous system connecting the brain and spinal cord.

This procedure left the child unresponsive, a result of her not being given any anesthesia during the procedure. Although she recovered, another tumor grew shortly after. As she continued growing, so did the two tumors, connecting to form one large tumor. The girl remained healthy physically and mentally, despite the tumor’s weight, which sometimes caused her to lose balance when her head was touched.

She eventually died at 17, the tumor having grown to an enormous size. After her death, Bennett gave the girl’s skull away to be studied, and his observations and the examination of the girl were published in the Baltimore Medical and Surgical Journal Review.

Neither the girl nor her mother decided how she would be treated. Their slave owner E.S. Bennett made these decisions for them, treating the girl as his personal specimen.

Abusing the ‘Most God-Like’ Sciences

Physicians would continue to perform medical experiments on enslaved people throughout the United States, seldom facing any repercussions, despite poor outcomes. In 1833, an unnamed enslaved woman in Missouri suffered a bout of spasmodic cholera, eventually making a full recovery.

However, a member of the Thomsonian System, an organization that promoted the use of alternative medicine and herbal remedies, misled the Missouri woman’s enslaver to believe that her cholera would recur, thus getting his permission—not hers—to perform an experimental treatment on her. The Thomsonian physician repeatedly administered lobelia and injected infused red pepper into her vagina, causing an infection. The woman was left extremely weak and was in excruciating pain for days due to necrosis and inflammation

Eventually, Thomas Jefferson White, M.D., arrived and treated the woman, and she made a full recovery. He wrote about this instance of malpractice to “stigmatize with infamy the ignorant pre-tender, who has thus abused the principles of the most god-like and useful of sciences.”

The Americas have a long history of medical experimentation of Black individuals, many of them unnamed, with procedures often performed without consent or anesthesia.

In the Buffalo Medical Journal in 1859, S.B. Hunt, M.D., denounced the foundational American belief that “all men are created free and equal,” claiming that it was an “anatomical, physiological and scriptural impossibility.” He relied on phrenology, the bogus use of head size as an intelligence indicator to justify horrific treatment of African slaves, citing a smaller cranial size and different cranial shape to classify them as a “low type of human organization.” The white doctor argued that setting them free would “place three and a half millions of an inferior race in competition with one far superior to it in anatomical perfection.”

Yet the medical experiments performed on Black slaves provided the foundation of American medicine as they were apparently similar enough to white individuals for the experiments to be applicable.

Today: Major Health Disparities

Today, African Americans have one of the lowest health outcomes in America as it relates to premature deaths, with Mississippi ranking last for the overall health for Black Americans. In Mississippi, 650.9 per 100,000 Black Americans die prematurely due to avoidable causes.

Mississippi as a whole is facing a medical crisis, yet it disproportionately affects Black individuals, as predominantly Black communities in Mississippi typically lack quality health-care resources, especially in rural areas. Mississippi’s decline followed resegregation efforts during the mid-to-late 1990s, when many white residents in integrated cities moved to the suburbs, taking their businesses and tax dollars with them. These cities, in return, had to raise taxes and cut some of their services.

“That’s why a lot of people want to move to or try to get to Madison and Ridgeland because they have these resources,” said Shelethia Whisenton, program manager for the Institute for the Advancement of Minority Health.

This phenomenon, known as white flight, left many cities in Mississippi without many, if any, options for food and health care.

“There are 32 hospitals that are up for being shut down,” said Markyel Pittman, also a program manager of the Institute for the Advancement of Minority Health. “It’s all about holding those people accountable because they’re … closing hospitals down in Black, rural communities.”

Research from the University of Chicago shows that hospital closures disproportionately affect Black and Brown communities. University researchers analyzed 6,500 hospitals across the United States and found “both socioeconomic disadvantage and majority Black racial composition of a healthcare service area increased the likelihood of hospital closure in that area.”

‘Our Health Is Not a Priority’

In Greenwood, Mississippi, a predominantly Black city, the Greenwood Leflore Hospital had been struggling to keep its doors open during a three-year financial struggle. It cut many of its services to stay afloat but was able to keep the doors open due to support from the Medicaid program. Moreover, 30% of rural hospitals in Mississippi were in immediate risk of closure in 2023, and many of these hospitals had to remove their inpatient services to stay afloat.

Currently, five hospitals in Mississippi are a part of Medicaid’s Rural Community Hospital Demonstration program, and of the individuals on Medicaid in Mississippi, 52.8% of them are Black. The passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act will render millions of people uninsured by 2034 due to its changes to Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act.

“Our health is not a priority,” Whisenton said.

Experts say major health disparities exist in Black communities due to the lack of access to quality health care, and finding quality health care is only made harder when hospitals in Mississippi are at a constant risk of being shut down and when citizens lack health insurance.

Black Mistrust of Medical Providers

In addition to the lack of quality health care, many Black Americans avoid going to the doctor’s office due to mistrust of health-care professionals.

“A lot of that goes back to the time where Tuskegee had its studies that were done and Black Americans were taken advantage of,” University of Mississippi Medical Center Assistant Professor Dr. Justin Turner said. “Although that was over 70 to 80 years ago, the remnants of that still linger in the minds of Black Americans.”

In the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, hundreds of African American men were left untreated for syphilis from 1932 to 1972, despite penicillin being widely available as early as the 1940s. The federal government wanted to determine the effects syphilis had on the body. The men were unaware they had syphilis, some dying as a result, and many of the participants became too old to receive treatment once the study ended.

The dark history of Black Americans in medicine created a generational mistrust toward doctors, leading many to not want to participate in clinical trials. Despite African Americans making up 12% of the population, only 5% of clinical-trial participants are Black, contributing to an overall under-representation in health care.

The underrepresentation of Black Americans has led to ignorance of Black health. “There have been studies that have been done, especially when it comes to minority populations, (that) Black individuals, in particular, can bear pain more,” said Alecia Reed-Owens, deputy director of health law at the Mississippi Center for Justice. “And so, if people really believe in this and go into the medical field, we may not get that same approach, and so we don’t want that to be taken as true.”

During the slave trade, enslavers preferred Africans from malaria-infested regions due to their resistance to malaria. Many of these enslaved people were resistant due to having sickle cell anemia and a G6PD deficiency. The slave trade caused malaria to rampage throughout the United States, killing many white Americans. Although many Africans were malaria-resistant, not all of them were, causing it to also take the lives of many enslaved people. The slave trade is the reason sickle cell anemia affects mostly African Americans in the U.S. today.

Around the same time, James Marion Sims, the “Father of Gynecology,” built his practice on the backs of enslaved women. In one of his operations, he experimented on an enslaved woman named Lucy, who was suffering from a fistula, and she contracted blood poisoning after he used a sponge to drain the urine from her bladder, something that was not standard practice.

Sims did not believe that Black women could feel pain, despite Lucy screaming throughout her procedure. Years later, once he perfected his practice, he moved on to treating white women using anesthesia.

RJK Jr.: ‘Their Immune System Is Better’

The exposure of non-immune African slaves to malaria and the belief that Black people do not feel pain are some of the earliest examples of ignorance of Black health, yet it is still prevalent.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services, has advocated that Black Americans should be put on a different vaccine schedule because “their immune system is better” than that of white Americans, which is not true. The author of the study RFK Jr. cites does not actually advocate for changing the vaccine schedule of Black Americans because—similar to the pain tolerance and resistance of enslaved Africans to malaria—it is a generalization, and the change is potentially dangerous to individuals if implemented.

Because of these stigmas, many African Americans prefer someone they can connect with to provide them with better care. “Many Black patients feel like a Black doctor may be able to understand their cultural differences,” Dr. Turner said.

Fifty-five percent of African Americans have reported that health-care professionals and the medical system have treated them unfairly.

Black adults with Black health-care providers report more positive interactions than those with non-Black health care providers, as there is a level of mutual understanding. Further, the life expectancy of African Americans is longer when they are treated in areas with a larger proportion of Black doctors.

The difference in care can be partly attributed to the apathy that many health providers possess. Humans naturally feel less empathy for those who they view different from themselves. For example, despite sickle cell disease affecting more individuals overall, cystic fibrosis receives more federal funding. Although both are autosomal recessive disorders, sickle-cell impacts mostly Black Americans, while cystic fibrosis mostly strikes white Americans.

Experts say that biases that health-care professionals hold can be mitigated by teaching health-care professionals to be sensitive early on in their education.

“At least (educate about biases) on the collegiate level if there’s any type of interest in the health law field because there are biases in all shapes, forms and fashion,” Reed-Owens said. “When people grow up in different types of families and communities, we all hold biases to some degree and (we should) just really reshape it so that we can have the best treatment.”

Improving the Odds

To close the health-disparity gap, many organizations have been working to provide quality health care to Black communities.

“We have been offering free health screenings, be it pap smears, mammograms, low-dose lung cancer CT scans. (We are) not just talking about it, but actually being about it and meeting the community where they are, building those relationships and building that trust,” Turner said.

Greater health-care options alone will not completely close the gap, as many social determinants of health have an impact on Black Americans in Mississippi.

“As attorneys, we come in because we want a holistic approach for these individuals to be healthy,” Reed-Owens said. “Not just being treated at the doctor’s—other things that come on that can compound their health issues. We talk about the mental, physical and emotional (aspects) of all these things.”

The Mississippi Center For Justice runs an economic-justice campaign that allows convicts to get jobs, supports primary and secondary education and aids individuals impacted due to natural disasters—all of which translates to them leading healthier lives.

When people face health-based discrimination, “the first thing that we want to do is we want individuals to know (they need) to get in front of someone that could properly advise,” Reed-Owens said.

Laws are in place to protect individuals from harm, and attorneys can advocate on the behalf of people who have been discriminated against, as long as they report it. Jesus“There has to be consequences if they’re not abiding by (laws),” Reed-Owens said.

Medical professionals will not face consequences if people do not report malpractice or discrimination.

“(Laws) add to the structure and stability of our country, of our communities,” Reed-Owens said. “When we have these laws in place, people can’t just go and do what they want to do just because. You will have more discriminatory acts. You’ll have biases continuing to really drive things and it’s just going to be all out of whack.”

Individual Prevention

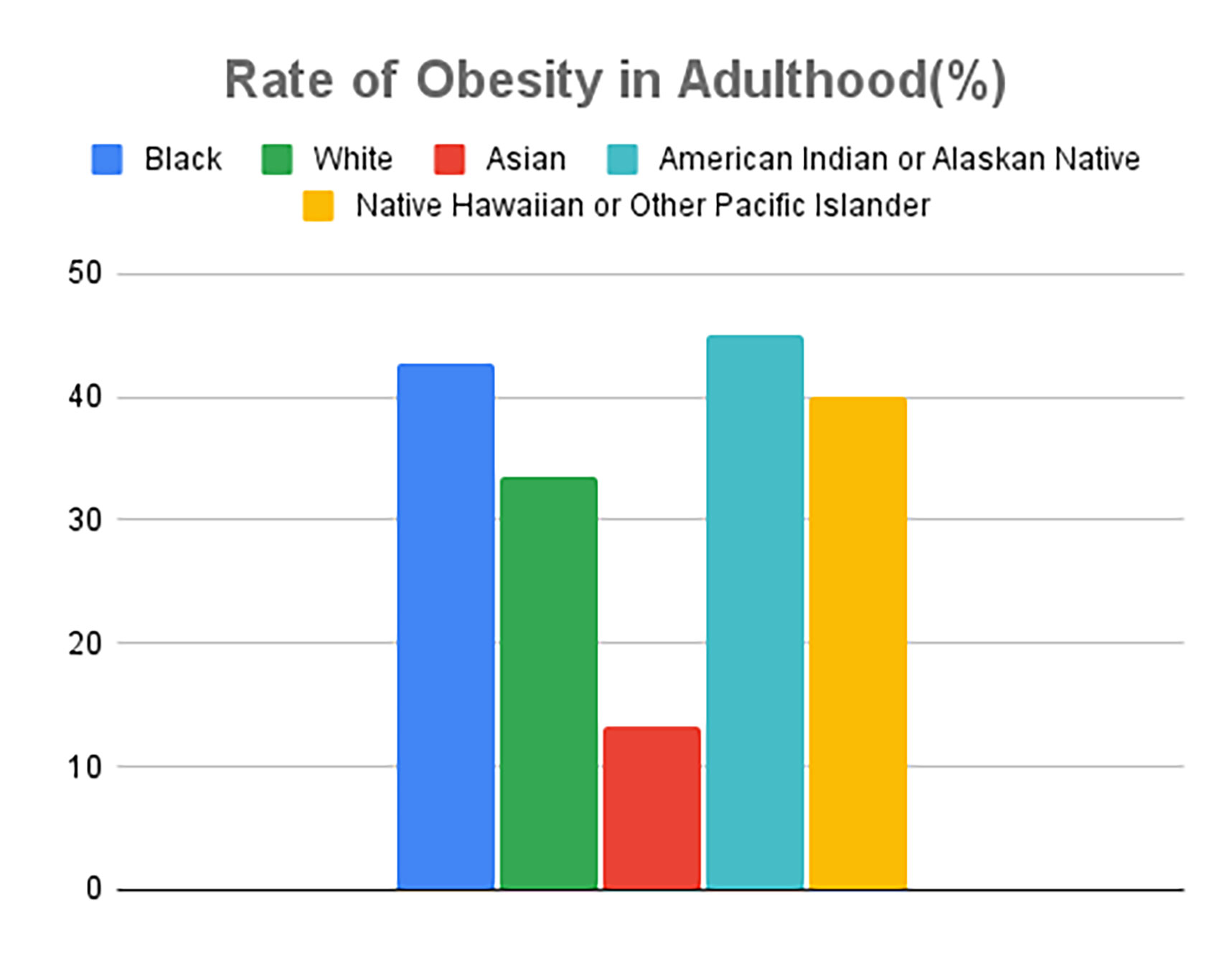

A change in individual mindset regarding health is required as well, as obesity and diabetes increase the risk of heart disease, the leading cause of deaths in Americans. About 43% of Black adults are obese and 13% have diabetes.

In 2020, only 29.7% of Black men and 16.5% of Black women met the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Regular exercise can help control weight and prevent the onset of conditions such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Dieting can also lead to a healthier lifestyle. “We eat to taste. We don’t eat for health or just to have the substance in our bodies,” Markyel Pittman said. Soul food is a large part of African American culture, yet it can lack healthy sustenance.

“Just because it’s part of the culture doesn’t mean it’s right,” Pittman said.

Preventing the onset of health concerns is better than treating them when they come. That may start with eating healthier. It can be difficult for people of different cultural backgrounds to diet because many diets exclude cultural foods, but there are ways to modify or regulate the consumption of cultural foods to be healthier.

“We are not even supposed to eat salt, but some people are going to add salt and pepper,” Whisenton said. Her advice: “Taste the food first.”

Modifying soul food to be healthier can start with using less sodium, using olive oil instead of butter or eating baked chicken instead of fried chicken. It can also consist of eating soul food in moderation instead of overindulging.

“To break the cycle, and it’s sad to say, sometimes we don’t learn better until worse comes on to us,” Pittman said. “We reduce health disparities through the young people. It can stop with us.”

Young people can bring about change by “being educated, passing it on, being open-minded and getting out of that mindset because we are the future,” Whisenton advised.