By Hannah Evans

Alecia Reed-Owens sat in a hospital bed wearing a hospital gown. She was in pain, and having been through delivery twice before, she knew she was ready to deliver.

However, the nurse who had just checked on her left the room after stating that Reed-Owens still had more time before the baby would come.

“Tell her to come back in or get someone else,” Reed-Owens, a native of Greenwood, Miss., said to her husband. “The baby is about to come.”

Her husband grabbed the nurse and urged her back into the room. Soon after, Owens gave birth to her third child.

Owens’ labor and delivery story is similar to that of many Black women. It is a harsh reality in America: White health-care providers often do not listen to Black patients.

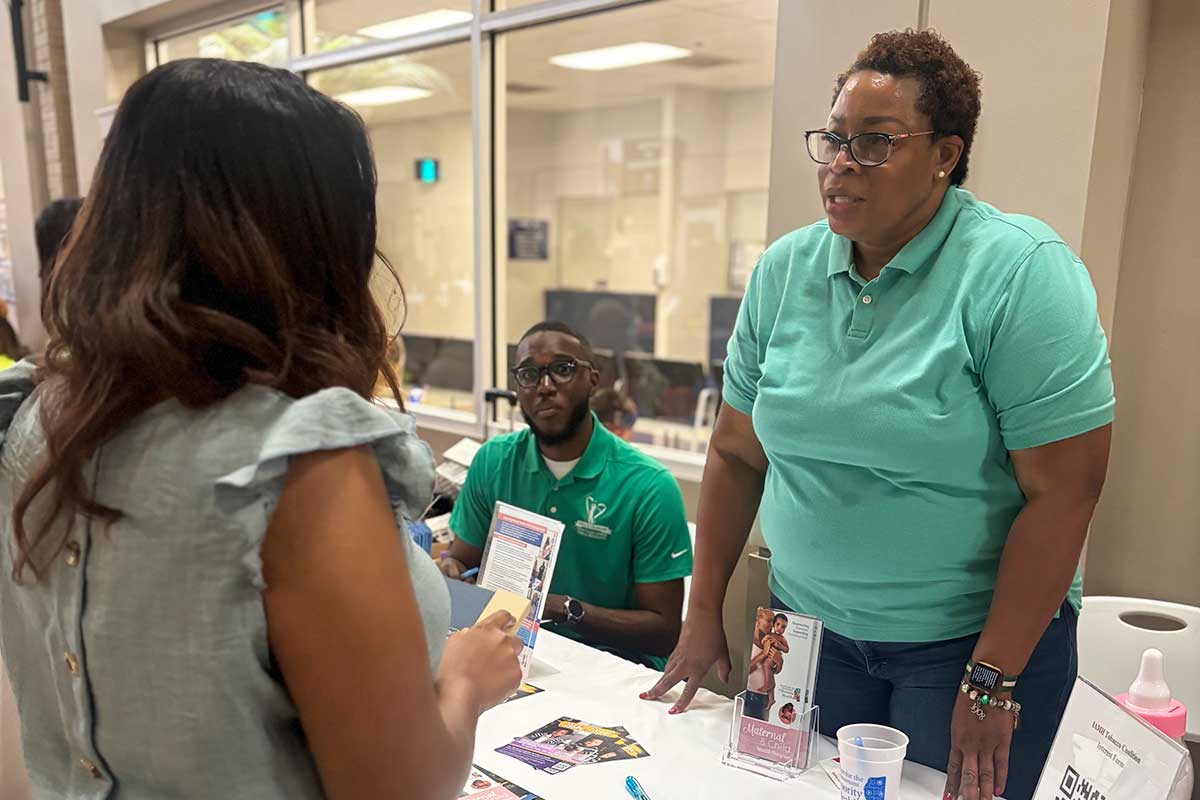

Now the deputy director of health law for the Mississippi Center for Justice, Owens explained to the Youth Media Project that the birth of her third child was just one of the times she had to fight to be heard regarding her health. Luckily, she has always had someone who could advocate on her behalf should she be unable; however, not all Black women have someone to speak up for them in these situations.

More Likely to Face Childbirth Complications

Black women’s reproductive health during medical checkups is often deemed unnecessary.

“I’ve gone to the OB-GYN since I was 18 years old, and no one ever asked important questions,” Mauda Monger, the CEO of the SHE Project and a public-health professional, said. Monger said that during her doctor visits, she was never asked, “Do you want to get pregnant?”

Monger believes her race was a factor in her reproductive health being overlooked. “ … It was probably because I’m unmarried and African American that I was never even asked those questions about true family planning,” she said in an interview.

Data from the National Library of Medicine show that Black women are three to four times more likely than white women to experience complications during pregnancy and childbirth. That often involves invasive procedures such as unwanted Cesarean sections, which can put them at risk for health complications.

Black women die at a higher rate than any other ethnic group during or after childbirth, making the importance of their voice in their treatment paramount.

Pew Research found that 71% of Black women ages 18 to 49 say they’ve had at least one negative interaction with a health-care provider, compared with 54% of Black women aged 50 and older, 51% of Black men aged 50 and older, and 43% of Black men aged 18 to 49. Whereas only 3.6% of white adults overall have felt discriminated against in their medical care.

Scarcity of Black Doctors Increases Distrust

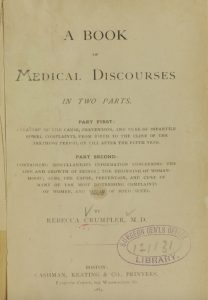

Mistreatment of Black women in health care can be traced back to historic racism within the health-care field, often resulting in ignoring health concerns and giving the bare minimum treatment to Black patients. In the past, this has resulted in actions such as not giving pain medicine to Black patients when needed.

Disparities in the medical care of Black people can be traced back all the way to slavery. Rebecca Lee Crumpler was born in 1831. Her aunt raised her, who took care of her many sick neighbors during slavery. Slaves didn’t have the resources to get proper treatment, and this influenced Crumpler to become a doctor. In 1864, a year after the United States passed the Emancipation Proclamation, she graduated from New England Female Medical College and became the first Black woman to earn her M.D. in the United States.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study is a significant example of racism in the health-care system. This unethical experiment, conducted from 1932 to 1972, involved nearly 400 Black men with untreated syphilis. None of the men consented to being tested and were given no treatment, which caused health problems, premature death and psychological trauma. This study created distrust of the medical field within the Black community, especially for Black men.

“The (Tuskegee) study’s methods have become synonymous with exploitation and mistreatment by the medical community,” Marcella Alsan from Stanford and Marianna Wanamaker of the University of Tennessee wrote in a working paper, “Tuskegee and the Health of Black Men” for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

This distrust can weaken Black people’s passion to become health-care professionals.

Although Black patients often prefer Black doctors, many don’t have the option, with 53% of Black people saying it’s hard to find a Black doctor. The Association of American Medical Colleges and others routinely report shortages of Black doctors and medical students, as well as low Black med-school enrollment.

As of March 2025, Black doctors comprised only 4.7% of U.S. physicians. This shortage presents fewer opportunities for people of color to find doctors who look like them. However, access to Black doctors requires more opportunities for Black people to attend medical school.

“The disparity matters, physicians, students, and others say, because doctors of color can help the African American community overcome a historical mistrust of the medical system—a factor in poorer health outcomes for black Americans,” USA Today reported in 2020 about the systemic disparity.

Before the summer of 2023, affirmative action in the college application process helped Black prospective students gain admission to institutions of higher learning. Affirmative action was aimed at increasing opportunities for historically marginalized groups in areas of employment and education. The U.S. Supreme Court reversed affirmative action in June 2023, and a decline in African Americans gaining admission to prestigious institutions followed.

Since then, it has been harder for Black people to get into prestigious higher education institutions. Harvard University experienced a decline in Black students in its most recent freshman class, with their enrollment dropping from 18% to 14%. Now, with the current administration cutting “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” programs, or DEI, and federal funding for education, those gaps could widen.

From Health Care to Legislation

The U.S. Congress recently passed the so-called “Big Beautiful Bill” into law, which President Donald Trump signed on July 4, 2025. The legislation significantly affects student loans, as it caps the amount graduate and professional students can borrow. This cap affects Black students nationwide, as financial cost is traditionally a barrier to education for people of color.

This bill reduces how much a student can borrow in a lifetime to $257,500. The average public medical school cost is $268,476, while private medical school costs $ 363,836. This means students will pay thousands of dollars out of pocket, and many may not be able to afford it, as 66% of Black students rely on student loans to complete their education.

If Black people cannot attend medical school, the lack of representation for Black people in health care will continue to grow.

Some legislation is designed to protect the health-care rights of marginalized groups. In the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VI prohibits discrimination by institutions that receive federal funding, such as hospitals.

U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren and Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, both Massachusetts Democrats, introduced a bill on April 10, 2025, to help address race disparities in medicine. The bill, known as the Anti-Racism in Public Health Act of 2025, would amend the Public Health Service Act and contribute to public-health research. It would also invest federal dollars into understanding and eliminating racism. The bill has yet to become law.

“By expanding research into the public health impacts of structural racism and requiring the federal government to develop anti-racist health policy, our bill is the type of responsive legislation the moment demands,” Pressley said about the bill.

Such legislation, as well as efforts to train aspiring doctors and nurses on anti-racism and to spot their own biases, could help women like Alecia Reed-Owens, even as it reinforces that Black medical providers and representation are essential to Black lives and good health care for all.

Reed-Owens said she may be an attorney, but she can still experience disparate and inadequate health care due to the racist beliefs of health-care workers. It is one of the reasons she works so hard to close the gaps.

“I’m going to need someone to treat me, and I want them to treat me well regardless of my degree, regardless of my skin color,” she said.

Read more about Youth Media Project student journalist Hannah Evans who wrote this piece during the summer 2025 class.