By Clay Morris

Indigo Williams and her then 5-year-old son, JS, were about to embark on the boy’s journey into the colorful and simple world of kindergarten in 2015. Beginning at Madison Station Elementary, a school with an “A” rating from the Mississippi Department of Education, Williams enrolled JS in multiple extracurricular activities, had access to tutoring, Taekwondo, fresh produce and basic necessities, such as toilet paper.

However, when Williams and her family moved ever so slightly out of their previous school zone, JS had to start in the Jackson Public School District where the quality of his education was to change dramatically. JS is now a student at Raines Elementary, a school rated “F” by the Mississippi Department of Education. Williams says JS’s school “feels more like a jail than a school. Paint is chipping off the walls. They’ve served him expired food in the cafeteria.”

Raines Elementary is 99 percent black, whereas Madison Station is 83 percent white.

Williams’ disgust with the conditions of Raines grew so strong that she and three other mothers of students at the school filed a lawsuit against Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant, State Superintendent of Education Carey Wright, Mississippi State Board of Education Chairwoman Rosemary Aultman, and a State Board of Education member, Jason S. Dean. Southern Poverty Law Center lawyers are helping with the lawsuit that was filed May 23, 2017.

The parents are arguing that the State of Mississippi has failed to provide uniform schools for children of all colors. The plaintiffs blame the weakness of the Mississippi State Constitution’s educational clause for the inequality in the state’s public-school system.

Ongoing Educational Funding Debacle

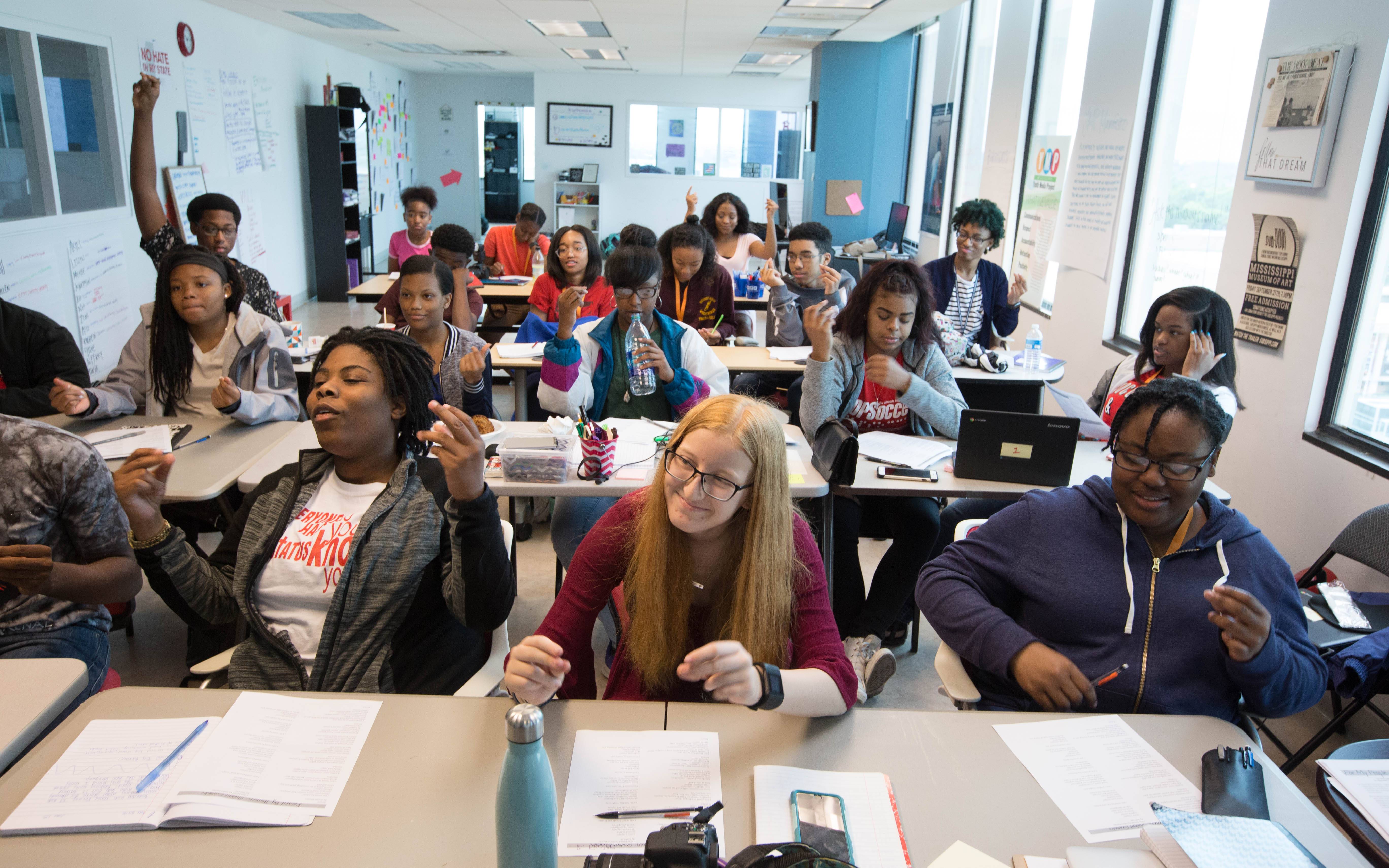

Maisie Brown is a 16-year-old student at Murrah High School, who previously attended Jim Hill High School. A former Youth Media Project student and now a mentor for current students, Brown is outspoken on the historic inequities in Jackson’s public schools compared to other public school districts with more resources, as well as the area’s private schools.

“I would like to see a level playing field. I don’t think I’ll see this in my time in JPS. Maybe when I’m in college, or maybe when my kids get ready to go to JPS. But, you literally cannot compare where you cannot compete,” she said. “I hope to see a Jackson that’s fully funded. I hope to see a Jackson with proper facilities. I hope to see a Jackson where every child is challenged.”

Part of this support must be from the State of Mississippi, she said.

“I mean, time after time we’ve been shown how little the State cares about JPS and how little is being done for the children of JPS,” Brown said. “We complain about crime in Jackson. We complain about poverty in Jackson. We complain about everything else in Jackson, but we’re still neglecting our schools. If we don’t give these kids the tools to be successful, then why do you think Jackson is the way it is?”

Inequitable education in Mississippi finds its roots somewhere between the gunpowder and gunshots of the Civil War. As slavery ended after the war and Reconstruction of the South began, so did the quest to establish education for all children in the Magnolia State. But a challenge stood confidently in the doorway of academia for the youth of 19th-century Mississippi: the prior relationship between black slaves, their white masters and education. Ongoing beliefs in white supremacy and fears about race-mixing left segregated schools with black children woefully unfunded and uneducated.

“After Reconstruction, you had this long period of time where black people were not in power in the Legislature,” Ed Sivak, vice president of the Board of Trustees of Jackson Public Schools, told the Youth Media Project.

Legally enforced segregation, and the peculiar strength that it was able to retain in Mississippi until the U.S. Supreme Court forced the state to integrate schools after Alexander v. Holmes County in early 1970, laid the groundwork for today’s unequal schooling system. The years prior to this date, and the flight of many white families, either to schools in the suburbs or academies, meant that young people in Jackson still suffer from an ongoing educational funding debacle that makes it difficult for many majority-black schools to get even the basics covered. The past has its hands slyly wrapped around the neck of the future.

Charles C. Bolton’s article, “Mississippi’s School Equalization Program, 1945-1954: A Last Gasp to Try to Maintain a Segregated Educational System” in the Journal of Southern History, reports that the Mississippi Association for Teachers in Colored Schools began its fight for the equalization of schools in Mississippi in the 1940s. Its members had to teach in conditions they deemed less than sufficient for the state constitution’s claim to “provide for the establishment, maintenance and support of free public schools.”

As World War II drew to a close, and the patriotism of the nation inspired a further exclamation of a need for the rights of black people in the state, the scramble to “equalize” education in the state increased. Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian C. Van Woodward’s “The Strange Career of Jim Crow” shows that worried white Mississippians saw a call for desegregation possibly rearing its head if the state of black schools was not adequately assessed. Thus, they frantically worked to build a facade of action to stop the manifestation of their greatest fear: equity between the races.

‘Children of the State’s Most Powerful People’

White people in Jackson were proud of Central High School in downtown Jackson since it had opened its doors in 1888. Central was a premiere public institution for the white elite in the state, and the plan was to keep it that way.

However, after Brown v. Board of Education had legally opened up the educational possibilities of black students in the state, the school was on a path for an interesting change. In 1969, when Brenda Walker and a handful of other black students arrived on Central’s campus, the idea that integration was a reality finally began to sink into the minds of white Mississippians.

Today, the Mississippi Department of Education—the state agency that recommended a takeover of Jackson Public Schools last year—is housed in the old Central High. It closed in Clay: I cannot find the date anywhere!! , as JPS had continued to shrink, and white residents moved further away from the city’s core. Wingfield High School in south Jackson was also a white school in its early days, as were Provine, Forest Hill and Callaway, all now almost completely black.

White families started fleeing Jackson after the 1970 Alexander decision, leaving gaping holes in abandoned neighborhoods, boarded-up shopping centers and a struggling school system as they decided to tiptoe away from their former homes in order to flee incoming black tenants, shoppers and students.

“After Alexander v. Holmes, 10,000 white students left from Mississippi public schools,” Civil Rights historian Robert Luckett, the director of the Maragaret Walker Center at Jackson State University, said in an interview. “That’s 40 percent of the schools’ population. And those were the children of the state’s most powerful people. Sixty percent of those kids end up in segregated schools created by the Citizens’ Council. Even the state’s very own governor, Phil Bryant, was a product of one of those segregationist schools.”

Public schools in Jackson now have a majority of black students, with the white students who do attend appearing as droplets of milk in a pool of obsidian liquid. The most diverse high school is Murrah, which still is more than 90 percent black now.

The reverse is true for schools in Madison, such as Madison Central with a 20-percent economically disadvantaged student body and a 30-percent minority student body. Germantown has a 22-percent economically disadvantaged population and a 20-percent minority population. Madison County is also home to several of the state’s wealthier private schools.

Funding was the next challenge for wandering whites, as the amount of money allocated to every school in each district is based off the amount of property tax revenue collected from inside that district. Currently, this way of justifying funding makes sense on paper, but the property taxes in today’s Jackson, since so much tax base fled beyond the city limits, are underwhelming, especially for a district serving many children living in poverty with additional needs. Mississippi Adequate Education Program’s (MAEP) local contributions are dramatically lower in Hinds County, the home of the capital city, than in nearby and wealthier Madison County.

The median household income of Jackson’s inhabitants is $41,754, whereas the median household income of Madison’s inhabitants is $98,567. The majority of Madison’s citizens leave their jobs in the capital city, dragging resources across the county line every day, accounting for the $56,813 difference that, in turn, translates into poorer educational facilities and opportunities, and a challenge attracting enough certified teachers.

The capital city with 137,716 black residents out of a population of 173,514, has more people than Madison, yet less funding for the children of the city with the largest black population.

Luckett says the unequal distribution of economic resources between the two districts in the state stems from racial tensions that have been a part of the greater nation as a whole since before its founding.

“Our Legislature is built up of the elite, and it has always been in their interest to continue to bolster the segregationist sentiments that have allowed them to sustain the way of life that they are comfortable with,” Luckett says.

Failing Facilities and Faulty Findings

Rayven Jones, a rising junior at Murrah High School in the Jackson district, was quietly walking to her debate class when she stopped to use her school’s bathroom. When she opened the door, she noticed a cracked white sink was sitting on the floor, as if that was where it belonged. As her eyes slowly traced down the walls that were a blue so faint they may as well have been white originally, she noticed a hole where the sink had been snatched down from its proper positioning.

“What happened to the sink?” she asked the gaggle of girls applying lip gloss and gossiping in the mirror.

“Oh, you know, that girl sat on it.”

Jones left the bathroom in disgust without using it.

Two months later when Jones returned to the same upper-level bathroom, the sink had not been moved. The school’s motto, “The Only Place To Be,” echoed through Jones’ mind as she stared at the broken sink on the floor, which to her represented the school’s failing facilities.

Jones’ experience is a common one in the 54 JPS schools.

Wright, Mississippi’s superintendent of education, told the Youth Media Project that the amount of money is not the core of public-schools’ issues, it is how they choose to spend the funds.

“Well, those are all local decisions that are made,” she said. “Every district has the responsibility for spending their funds the way their funds need to be spent. There are some districts that put more money into facilities than others.”

The current formula derived from the Mississippi Adequate Education Program (MAEP) provides funding to districts that are actually locally wealthy enough to be exempt from the federal funding process, but because they are not, less advantaged districts receive the same amount of federal funding when perhaps they could be receiving more.

Additionally, the State of Mississippi has funded MAEP only twice since its creation in 1997.

As a result, the quality and quantity of textbooks, access to technology, and upkeep for necessities such as toilet paper and soap in the restrooms of Jackson’s public schools are extremely lacking. “I do see how legislators could help. There have to be small steps before we get to our bigger picture,” Wright said.

Jessica Styres of Madison Central said she believed that students in Madison County’s public schools would like to see the districts helping each other to make schools more equitable. “I think that schools with more resources would and could (help). I can’t speak for my administrators, but I know, or at least hope, that the students would want to,” she said.

But Murrah High School teacher Sarah Ballard was less optimistic: “When it comes down to it, the people who live in Madison want to live in Madison, and they want their kids to go to Madison schools. If coming together means taking that away from [Madison residents] at all, I don’t see that happening.”

Jackson voters will decide on a $65-million bond initiative on Aug. 7, 2018. The vote would allow the release of funds adequately proportioned to every school in the Jackson district to account for specific damages to facilities in each school. Local residents would not see tax increases to pay for it.

If approved, JPS high schools would get $39,420,000 of the money. On average, each of the high schools would see about nine repairs apiece, with Callaway having 18, from site drainage and to soil erosion control to bleacher repair. Elementary-school repairs would total $14,355,000, with middle-school repairs amounting to $11,225,000.

Jackson City Council President Melvin Priester Jr. and JPS Board Vice President Ed Sivak both believe the bond could bring change to JPS. “I’m seeing a lot of positive change,” Priester said in an interview. “I’m seeing a lot of reinvestment from the community. It’s a difficult task, but I’m feeling more positive about JPS than I have in a long time.”

“A vote for this bond is a vote for our students,” Sivak told the Youth Media Project.

Others, such as Ward 3 Councilman Kenneth Stokes, are suspicious about how the money would be spent. “We don’t want to be tricked,” he said during a council meeting.

In response to that concern, the JPS board announced in late July that it is setting up a bond oversight committee to monitor how the money is allocated and spent.

Opportunity Knocks … for Some

Wearing a Speech and Debate T-shirt and blue jeans, 16-year-old Jessica Styres was prepared for a day of no school when WJTV interviewed her April 20, 2018, about the anti-gun violence demonstration she had organized earlier in the school year. She gave each of Madison Central’s 1,324 students 17 brightly colored Post-it notes, asking them to write inspiring messages and encouraging thoughts to decorate the schools’ muted nude walls.

By the time Styres had sorted through all the notes to check for any degrading commentary, the walls of Madison Central had turned into a rainbow of paper and ink. Styres looked it over with a satisfied smile.

Styres’ process to begin an anti-gun platform was smooth in comparison to how her peers in the Jackson district would have to approach a similar situation. She calls her school “a very encouraging place” with an environment that “generally seeks to better itself.”

Shaddia Lee of Murrah High School says her experience trying to hold a Valentine’s Day dance was nothing close to the silkiness of Styres’ event’s execution. Instead, Lee faced massive red tape.

“We have to go through a whole bunch of procedures and write out an answer to this large prompt and take it to our principal,” Lee, a 2018 Youth Media Project student, said. “It’s not like we’re even applying to get money for it, because after all that, you still have to fundraise for it yourself. Sometimes it will get approved, or it won’t get approved. If it’s something huge like what Jessica did, ha, we’d have to ask the entire district.”

Meanwhile, at schools including Provine High School in Jackson, students cannot even talk to each other at lunch, and the students are subjected to prison-like discipline in between and during classes, as they are also not allowed to talk in the hallways while changing class.

At Murrah, students say a distinct line is drawn between students who are a part of the Academic and Performance Arts Complex program (APAC), and those who are not–making many students feel pushed to the side.

“We have to stop acting like APAC and IB (International Baccalaureate) students are the only smart students in the school,” Brown said. “We can’t fully rely on the APAC and IB students to hold up the school. The majority of the Jackson district is not APAC, so why are we letting the rest of the district’s population fall through the cracks?”

However, the Jackson district offers 27 advanced-placement courses on its choice cards to high school students, while the Madison district offers 25. But many JPS students feel as if they are at a restaurant where they are presented with a myriad of options, but are routinely denied their requests.

Cameron Lazard, for instance, was walking through the small hallways of Callaway High School when she stopped at the wooden door of her counselor’s office to make a request. As she walked past the door and glided across the floor in her Nikes, she began to greet the counselor in front of her.

“Can you please switch Mississippi History from the bottom of my schedule to the top?” Lazard asked.

“I’m sorry. We don’t take Burger King requests!” the counselor answered. A security guard erupted in laughter with the counselor.

Lazard’s schedule remained an inconvenience for the rest of the school year. “When the students request things, they don’t want to help you at all,” she said of the school’s administration.

Teasing Through Testing

At the end of this article, there will be a test based on the contents that you have just read. If you answer fewer than 65 percent of the questions correctly, you will lose your job and not get another check.

The same way job anxiety and pressure just lumped together in the base of your chest is representative of how a majority of Mississippi public-school students and teachers feel about state testing.

The 66-page Student Assessment Handbook published on the Mississippi Department of Education website, has 14 points that discuss the specifics of administering state tests. Teachers say the stringency of these points, and the rigidity that follows with their enforcement, is troubling because it seems to restrict their ability to expressively teach Mississippi’s curriculum. The tests also burden students with the threat of not being admitted to a higher grade if they fail the assessment.

“The part of my job that needs improvement is dealing with high-stakes testing,” teacher Sarah Ballard of Murrah said. “There’s a lot of pressure for the students to score advanced, and sometimes the pressure comes from the district level. They think that we should be teaching them to the test. And it’s frustrating for me to have someone else kind of dictating what I should be teaching and how.”

Brown, who has experienced state testing three times, feels that it is unfair to try tp quantify the quality of a student based off their test scores. “Just because you can’t pass a test created by a company that the state has paid millions of dollars to create doesn’t mean you aren’t capable,” she told the Youth Media Project.

Standardized testing does not assess capability, both teachers and students say. “I think that I did much better on my AP tests than on my state tests,” Lazard said about her advanced-placement exams.

Both AP tests and the state assessments are standardized, but to Lazard, there seems to be a dysphoria between her state test materials and regular class materials. The learning that she is required to do for her AP tests, she thinks, is clearer and more linear in its instruction.

Germantown High School in the Madison district has an above 60-percent reading proficiency rating, which is at least 20 percent above the state rate and approximately 15 percent above the district’s level. In mathematics, Germantown is slightly above 20 percent proficient, which is slow for the state overall, but above average for the district. Only 32 percent of the population at Germantown are minority students.

In comparison, Lanier High School in the Jackson district barely rises above 5 percent for its reading proficiency rating and, as a result, trails behind the state 35 percent and the district by 10 percent. Lanier’s mathematics average sweeps the ground at 2 to 3 percent, which is 33 percent behind the state rate, and 1 percent below the district level. Only people of color are enrolled at Lanier.

Sivak, the JPS board vice president, seemed able to contextualize the almost irreconcilable inconsistencies in Mississippi’s history with racial history. “One of the modern-day realties is that we have school districts in the state—almost half majority black, almost half majority white,” he said. “When you look at the majority-white districts, roughly seven out of 10 of those districts are rated “A” or “B.” When you look at the majority-black districts, only one out of 10 are rated “A” or “B.” It’s hard for me to separate the history and the lawmaking that went into the realities that we have today.”

The Jackson City Council president is uneasy with the testing requirements. “We definitely have an over-reliance on testing. We like to test because it seems to create a quantifiable base to compare schools and compare achievement. I think that the main people testing has benefited are the companies that sell the tests,” Priester said.

Madison still manages to come out on top of required testing. “Our teachers don’t teach the test as much as other schools’ teachers do. Our teachers teach to AP test. But I do think that [being taught to test] hampers a lot of students if you can’t put that behind you,” Styres of Madison Central said.

It likely has something to do with teacher quality. Chronically under-funded schools with crumbling facilities not only affect students’ ability to learn, their feelings of stability, safety perceptions and other factors, but they have a harder time attracting and keeping quality teachers who bring creativity and passion to the classroom.

“I don’t know a single bad teacher at Madison Central. All around, I think it’s just like a well-rounded school. I was going to go to Jackson Prep when I was little, but my parents are always like, ‘We moved to Madison so that you could have a better education,'” Styres said.

Brown said leaders on the state level need to believe that children in Jackson deserve the same paths to success that Madison County students have. “I believe that we first have to be awarded the opportunities that other districts are awarded,” she said. “JPS needs to have more leaders and people in power that actually care about students.”

Likewise, Indigo Williams, the mother who sued the governor last year over disparities, is dissatisfied with opportunities in the Jackson public school that her son attends.

“He does not have any of these resources at Raines,” she said at a Southern Poverty Law Center press conference. “This sends a horrible message to my son that the type of education he gets depends on the color of his skin and the race of the other children in his school.

“What a horrible lesson to teach a 6-year-old.”

Clay Morris is a senior at St. Andrew’s Episcopal School and a 2018 Youth Media Project student journalist. Additional reporting by Janesha Bryant, Dyadha Nolan, and Inajas Perry.